AVALIAÇÃO DA IMDb

7,7/10

24 mil

SUA AVALIAÇÃO

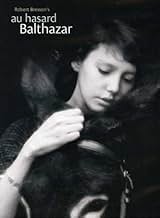

A história de um jumento maltratado e das pessoas ao seu redor. Um estudo sobre santidade e uma peça que faz relação com "Mouchette, a Virgem Possuída", também de Robert Bresson.A história de um jumento maltratado e das pessoas ao seu redor. Um estudo sobre santidade e uma peça que faz relação com "Mouchette, a Virgem Possuída", também de Robert Bresson.A história de um jumento maltratado e das pessoas ao seu redor. Um estudo sobre santidade e uma peça que faz relação com "Mouchette, a Virgem Possuída", também de Robert Bresson.

- Prêmios

- 7 vitórias e 2 indicações no total

Mylène Van der Mersch

- Nurse

- (as Mylène Weyergans)

Avaliações em destaque

The star of Au hasard Balthazar is a donkey, a trained animal that has been led, goaded, into what passes, in an animal sense, for a performance. Of course there is nothing new about this - animals have been stars since Rescued By Rover - yet there is something unique about the performance of the donkey in Au hasard Balthazar, something that strikes one sort of funny if one gets to thinking about it. It has to do with the approach of Robert Bresson, a director whose way of working with actors was, shall we say, unusual. An auteurist in the purest sense, Bresson believed, zealously it seems, that the director should be the sole creative force behind a film, the one person responsible for the movie's tone, its meaning. The problem with most movies, if you look at things in a Bressonian way, is that stubborn habit of actors to sometimes change the meaning, the texture of a scene by how they play it - that irksome tendency of actors to take the creative reins themselves, and slip things into scenes that aren't meant to be there. Bresson's solution to this problem? Rehearse your actors to death, make them do take-after-take until the words no longer mean anything to them, until they have lost the ability to be spontaneous anymore, to do anything but what their director tells them to - in short, break them like animals. The people in Bresson's films perform their actions with the same hollow, mechanical absence-of-will one perceives in a circus elephant rolling a ball, and this is exactly as Bresson wants it, for it allows him to carry out his cinematic plans without fear of their being subverted by an actor who has some contradictory notion in their head of what a scene is supposed to be about, who their character is. The human actors in Au hasard Balthazar, stripped of their emotional tools, their tricks, occupy exactly the same plane as the donkey Balthazar, who is, as they are, a trained animal, an element in a composition.

The first scenes are an idyll: the foal Balthazar, new-stripped from his mother's teat, becomes the favorite pet of a group of kids spending the summer together on a farm. This is a time for frolicking, for amorously carving names into benches - but alas the childish harmony is doomed soon to end. Bresson conveys the fleetingness of youth, cutting quickly through a series of tableaux depicting carelessness and joy slightly darkened by the presence of a sickly young girl; then without warning we're presented with the realities of grown-up existence, embodied most cruelly by the image of poor Balthazar, now grown, harnessed to a salt-wagon (salt having ironically been his favorite treat during his care-free younger days). It's here that Bresson gives us an indication as to the donkey's more-than-animal nature: Balthazar, having been mistreated, rebels against his owner, tips the wagon and, about to be set upon by a mob of men with pitch-forks, flees. Some instinct - or is it conscious will? - leads Balthazar back to the farm, which has been taken over by a former schoolteacher whose daughter, Marie, once one of Balthazar's playmates, still resides, her existence a lonely one. This would seem the beginning of a new happiness for Balthazar, but the donkey's fate is alas still clouded with gloom. Marie becomes the object of the juvenile delinquent Gerard's amorous attentions; for obscure reasons the jaded miscreant is resentful of Balthazar, and avails himself of every opportunity to torture the poor beast.

Tenderness and cruelty live side-by-side in Au hasard Balthazar, and seem equally the product of an almost mindless instinct. Nowhere is this embodied more purely than in the character of Gerard (Francois Lafarge), the angry sadist who becomes Balthazar's chief tormentor. Gerard is capable of being gentle, as demonstrated by his wooing of the poor farm-girl Marie (the Pre-Raphaelite beauty Anne Wiazemsky), but he's equally capable of unfeeling viciousness, as when he ties a piece of newspaper to Balthazar's tail and sets it alight. Is Gerard a good person or a bad one? Does he hate Balthazar, does he love Marie? These questions seem of little concern to Bresson, who views human affairs in terms of irresistible internal forces. Bresson, in a mysterious, vaguely irreverent way, blurs the line between human and animal, brings human behavior into the animal world while elevating Balthazar to the quasi-human. There's an awareness to Balthazar that's more than you would expect from your average quadruped, and it's through this hint of sentience that one begins seeing the saintly qualities in Balthazar, the patient endurance of hardship, the radiance of spirit.

It's an amazingly delicate piece of work by Bresson, an audacious idea carried out with the utmost discretion and skill. Perhaps only Bresson among all filmmakers could've made this idea work, because only he had mastered the art of rendering existence nearly abstract while at the same time achieving powerful emotional effects. If the film were merely symbolist it would be irrelevant - Balthazar can of course be seen as a symbol for a lot of things, but it doesn't seem right to reduce him to some emblem of suffering, some Christ-like trope. Balthazar is above all a character, a protagonist in a drama, but of course in Bresson there is never any sense of conventional drama, of easy emotion. As a storyteller Bresson was efficient but patient - his scenes never go on longer than they need to, yet you wouldn't call the pacing urgent. There's something about Bresson's cutting that keeps the story flowing briskly while never engendering a sense of hurry. He moves from one character to another, one situation to another, with an unfussy ease that shames most conventional directors with their dependence on transitions, devices and segues. The film's very pace helps convey Balthazar's saintly nature, his perseverance. It's a work at once touching, bold, enigmatic and stirringly human.

The first scenes are an idyll: the foal Balthazar, new-stripped from his mother's teat, becomes the favorite pet of a group of kids spending the summer together on a farm. This is a time for frolicking, for amorously carving names into benches - but alas the childish harmony is doomed soon to end. Bresson conveys the fleetingness of youth, cutting quickly through a series of tableaux depicting carelessness and joy slightly darkened by the presence of a sickly young girl; then without warning we're presented with the realities of grown-up existence, embodied most cruelly by the image of poor Balthazar, now grown, harnessed to a salt-wagon (salt having ironically been his favorite treat during his care-free younger days). It's here that Bresson gives us an indication as to the donkey's more-than-animal nature: Balthazar, having been mistreated, rebels against his owner, tips the wagon and, about to be set upon by a mob of men with pitch-forks, flees. Some instinct - or is it conscious will? - leads Balthazar back to the farm, which has been taken over by a former schoolteacher whose daughter, Marie, once one of Balthazar's playmates, still resides, her existence a lonely one. This would seem the beginning of a new happiness for Balthazar, but the donkey's fate is alas still clouded with gloom. Marie becomes the object of the juvenile delinquent Gerard's amorous attentions; for obscure reasons the jaded miscreant is resentful of Balthazar, and avails himself of every opportunity to torture the poor beast.

Tenderness and cruelty live side-by-side in Au hasard Balthazar, and seem equally the product of an almost mindless instinct. Nowhere is this embodied more purely than in the character of Gerard (Francois Lafarge), the angry sadist who becomes Balthazar's chief tormentor. Gerard is capable of being gentle, as demonstrated by his wooing of the poor farm-girl Marie (the Pre-Raphaelite beauty Anne Wiazemsky), but he's equally capable of unfeeling viciousness, as when he ties a piece of newspaper to Balthazar's tail and sets it alight. Is Gerard a good person or a bad one? Does he hate Balthazar, does he love Marie? These questions seem of little concern to Bresson, who views human affairs in terms of irresistible internal forces. Bresson, in a mysterious, vaguely irreverent way, blurs the line between human and animal, brings human behavior into the animal world while elevating Balthazar to the quasi-human. There's an awareness to Balthazar that's more than you would expect from your average quadruped, and it's through this hint of sentience that one begins seeing the saintly qualities in Balthazar, the patient endurance of hardship, the radiance of spirit.

It's an amazingly delicate piece of work by Bresson, an audacious idea carried out with the utmost discretion and skill. Perhaps only Bresson among all filmmakers could've made this idea work, because only he had mastered the art of rendering existence nearly abstract while at the same time achieving powerful emotional effects. If the film were merely symbolist it would be irrelevant - Balthazar can of course be seen as a symbol for a lot of things, but it doesn't seem right to reduce him to some emblem of suffering, some Christ-like trope. Balthazar is above all a character, a protagonist in a drama, but of course in Bresson there is never any sense of conventional drama, of easy emotion. As a storyteller Bresson was efficient but patient - his scenes never go on longer than they need to, yet you wouldn't call the pacing urgent. There's something about Bresson's cutting that keeps the story flowing briskly while never engendering a sense of hurry. He moves from one character to another, one situation to another, with an unfussy ease that shames most conventional directors with their dependence on transitions, devices and segues. The film's very pace helps convey Balthazar's saintly nature, his perseverance. It's a work at once touching, bold, enigmatic and stirringly human.

During the nineteenth century ,the comtesse de Segur wrote a novel for the children called "memoirs of a donkey" .A very pious writer,she chose the donkey as a symbol of humility...as Robert Bresson did I suppose.The very first pictures of the movie,with the children,"christening" the donkey ,might be a nod to the writer whom the young Bresson,like all his generation must have read when he was a young boy."Au hasard Balthazar " is an updated version of "les memoires d'un ane" ,but a very austere story:although Bresson's work enjoys a very high rating on the site,I must say that it's not for all tastes.I cannot imagine,say, a "matrix" fan getting enthusiastic about it.

Bresson's actors are non -professionals -with the exception of Anne Wiazemski,but it was her debut;then she became the par excellence intellectual actress,for the likes of Godard,Tanner and Garrel,all directors that easily make me yawn my head off-,but do not expect a "natural "performance.I hope the non-French speaking who wrote a comment saw the movie in French with English subtitles.Dubbed in another language ,Bresson's works lose a lot of their originality.Because the actors speak in a distant voice,in a neutral style as if they were reciting Descartes's "the Discourse on Method".They never show any emotion,even through their darkest hour (not even after the heroine's rape).

Bresson films his human characters as if they were Martians ,and his sympathy for the donkey is the only pity he has to give us.This beast of burden seems to carry on its back all the sins of the world,and his route is a calvary.A woman says "this donkey is a saint" .

Bresson showed us the Beast in Man and the Man in Beast.

Bresson's actors are non -professionals -with the exception of Anne Wiazemski,but it was her debut;then she became the par excellence intellectual actress,for the likes of Godard,Tanner and Garrel,all directors that easily make me yawn my head off-,but do not expect a "natural "performance.I hope the non-French speaking who wrote a comment saw the movie in French with English subtitles.Dubbed in another language ,Bresson's works lose a lot of their originality.Because the actors speak in a distant voice,in a neutral style as if they were reciting Descartes's "the Discourse on Method".They never show any emotion,even through their darkest hour (not even after the heroine's rape).

Bresson films his human characters as if they were Martians ,and his sympathy for the donkey is the only pity he has to give us.This beast of burden seems to carry on its back all the sins of the world,and his route is a calvary.A woman says "this donkey is a saint" .

Bresson showed us the Beast in Man and the Man in Beast.

A truly unique work in cinema. It is simply amazing that a story that is, on the surface, mostly about the life of a donkey can cause you to ponder the mysteries and ironies of life and fate. Bresson created here a model of how to say more with less. The final scene of this film is illustrative of this in its extraordinary ability to deeply move the viewer with only a bare minimum of directorial touch.

The plot lines of Au Hasard Balthazar at times seem forced, sometimes confusing the viewer, and often leaving the characters' motivations unexplained. This matters little, however, because they all follow the same theme that one's actions, explainable or not, are often just a reaction to the environment within which we are placed. The human characters and the donkey are one. Just as Balthazar must succumb to the whims of his owners, so are we humans often just surviving, and submitting to, the actions of those who control us. The film is in many ways a rumination about the free will actually afforded us in life. A key scene is between Marie and the miserly farmer (winemaker?), where the latter expounds upon his philosophy. Money and self-confidence are the keys for him because they allow a certain autonomy that lets him do as he pleases. Money, or the lack thereof, is depicted in several instances as often replacing true morality or spirituality in the characters' lives.

Another scene that mesmerizes (there are several) is when Balthazar is pulling the circus-animal feeding cart through the cage area. The soundless shots of the donkey making eye contact with the other animals is brilliantly done (again with little camera flourish). They seem to be communicating silently with only their gazes, which say "here we are, this is our fate". Extremely affecting, and staggering in its simplicity.

This is a film to be watched again and then again, and then again. In one of the DVD extra features, film scholar Donald Ritchie states that he has seen Balthazar many times, yet he still cries during the ending. I believe this and understand it. Credos to Criterion for resurrecting this classic, and for again doing such a fine production job.

The plot lines of Au Hasard Balthazar at times seem forced, sometimes confusing the viewer, and often leaving the characters' motivations unexplained. This matters little, however, because they all follow the same theme that one's actions, explainable or not, are often just a reaction to the environment within which we are placed. The human characters and the donkey are one. Just as Balthazar must succumb to the whims of his owners, so are we humans often just surviving, and submitting to, the actions of those who control us. The film is in many ways a rumination about the free will actually afforded us in life. A key scene is between Marie and the miserly farmer (winemaker?), where the latter expounds upon his philosophy. Money and self-confidence are the keys for him because they allow a certain autonomy that lets him do as he pleases. Money, or the lack thereof, is depicted in several instances as often replacing true morality or spirituality in the characters' lives.

Another scene that mesmerizes (there are several) is when Balthazar is pulling the circus-animal feeding cart through the cage area. The soundless shots of the donkey making eye contact with the other animals is brilliantly done (again with little camera flourish). They seem to be communicating silently with only their gazes, which say "here we are, this is our fate". Extremely affecting, and staggering in its simplicity.

This is a film to be watched again and then again, and then again. In one of the DVD extra features, film scholar Donald Ritchie states that he has seen Balthazar many times, yet he still cries during the ending. I believe this and understand it. Credos to Criterion for resurrecting this classic, and for again doing such a fine production job.

To read through most reviews of Balthazar feels like having stepped inside a church with people sighing about god and transcendence, which is a testament to Bresson's power here in his most spiritual work so far. But let me step outside in clear air for a moment.

It was an ongoing project for him, striving for an ascetic eye that purifies. He had began (essentially) with Diary of a Priest, ambitious work about a spiritual journey. But I believe he was troubled by a few things in it, if his next films offer any clue.

He spent the next couple of films completely muting the emotional turmoil evident in Diary, taking all the romanticism out, making them purely about the desire to break free from a prison-world. Pickpocket and Jeanne D'Arc were sketches in that austere direction. But this was setting him down a disastrous path where the only thing purer was was just more and more bare. When does fasting become starving and why is a stone floor purer than a furnished house?

How about we say that his desire to evoke the abstract was laudable, but his dogmatic way of doing it absolutely killed the world in which it lives and hides? His camera murders it. It only managed to take the pure out of life and make a liturgy around its dead body. It was destroying the possibility for cinematic space to support metaphor, inner life, poetry, and to simply be anything other than dead nature. The process of facts alone won't do, they can never convey life, much less pure life.

So I had my sights set on Balthazar as his most pure, most lauded, and expected perhaps to mount a critique of a spirituality that is only its own funeral. But I believe he beat me to the punch. I believe he began to see that he was starving himself, at least so far as the film is different from before.

This is his most lush, his most ambitious since Diary (none of the interim were), his most accomplished and with the most life. His camera doesn't just stare, it moves again and searches. He doesn't just create ellipsis within a scene, he makes it move across the narrative.

A household collapses, but we move to see this in the girl's disastrous relationship with a despicable bully, and we experience the loss of innocence, the fouling of kindness in her world, in Balthazar's treatment at the hands of several callous owners.

At the center Bresson has the most placid, most unassuming actor, a selfless being. It's by reading what we do in Balthazar's eyes that we color the whole and it ripples through and becomes ours. We have the reactions he doesn't and thus humanize ourselves. It's marvelous and it plumbs into something fundamental about how the world is put together that makes it worthy beyond technique.

See, life will break down, sometimes for no other reason than someone changed his mind about a deal and pride. It will break and scatter in pieces, go through the cycle of suffering. The film ends with everything broken, nothing put back together, the girl having left off for a next life somewhere.

What it plumbs is that what we see into these makes a difference. There's abandonment at the end, heartbreak, anonymous loss of a soul that we knew as dear. But I would rather see courage myself. Instead of projecting our human terror into him, take from his capacity to endure. If suffering isn't pain, it's not being able to abide pain; how about there is nothing lost, nothing broken, there is only a time for things to come together and a time to disperse again? Balthazar isn't lost, he has returned, or so it goes maybe.

It was an ongoing project for him, striving for an ascetic eye that purifies. He had began (essentially) with Diary of a Priest, ambitious work about a spiritual journey. But I believe he was troubled by a few things in it, if his next films offer any clue.

He spent the next couple of films completely muting the emotional turmoil evident in Diary, taking all the romanticism out, making them purely about the desire to break free from a prison-world. Pickpocket and Jeanne D'Arc were sketches in that austere direction. But this was setting him down a disastrous path where the only thing purer was was just more and more bare. When does fasting become starving and why is a stone floor purer than a furnished house?

How about we say that his desire to evoke the abstract was laudable, but his dogmatic way of doing it absolutely killed the world in which it lives and hides? His camera murders it. It only managed to take the pure out of life and make a liturgy around its dead body. It was destroying the possibility for cinematic space to support metaphor, inner life, poetry, and to simply be anything other than dead nature. The process of facts alone won't do, they can never convey life, much less pure life.

So I had my sights set on Balthazar as his most pure, most lauded, and expected perhaps to mount a critique of a spirituality that is only its own funeral. But I believe he beat me to the punch. I believe he began to see that he was starving himself, at least so far as the film is different from before.

This is his most lush, his most ambitious since Diary (none of the interim were), his most accomplished and with the most life. His camera doesn't just stare, it moves again and searches. He doesn't just create ellipsis within a scene, he makes it move across the narrative.

A household collapses, but we move to see this in the girl's disastrous relationship with a despicable bully, and we experience the loss of innocence, the fouling of kindness in her world, in Balthazar's treatment at the hands of several callous owners.

At the center Bresson has the most placid, most unassuming actor, a selfless being. It's by reading what we do in Balthazar's eyes that we color the whole and it ripples through and becomes ours. We have the reactions he doesn't and thus humanize ourselves. It's marvelous and it plumbs into something fundamental about how the world is put together that makes it worthy beyond technique.

See, life will break down, sometimes for no other reason than someone changed his mind about a deal and pride. It will break and scatter in pieces, go through the cycle of suffering. The film ends with everything broken, nothing put back together, the girl having left off for a next life somewhere.

What it plumbs is that what we see into these makes a difference. There's abandonment at the end, heartbreak, anonymous loss of a soul that we knew as dear. But I would rather see courage myself. Instead of projecting our human terror into him, take from his capacity to endure. If suffering isn't pain, it's not being able to abide pain; how about there is nothing lost, nothing broken, there is only a time for things to come together and a time to disperse again? Balthazar isn't lost, he has returned, or so it goes maybe.

For all its formal brilliance, this is one of the least watchable films in the world, despite its enchanted opening and fairy tale elements. Seen through the eyes of a much-abused donkey, we are treated to a litany of corruption, legal (a man is accused of fraud), social (provincial France has never seemed so pinched, arid, spiritually void, with its inhabitants leading lives, in Joyce's words, of 'quiet desperation'), criminal (a gang of violent teenage smugglers), and personal (the leader of said gang rapes, with his cronies, his girlfriend, then locks her up naked), as well as a murder and suicide. What makes this possibly bearable is the limpidity and formal beauty of Bresson's style, and admirers refer to his pinpointing spiritual grace in human suffering, but I wouldn't count on it.

Você sabia?

- CuriosidadesBalthazar was an untrained donkey during most of the filming, which made Robert Bresson's work a real challenge. The only scene for which the donkey was trained was the circus math trick.

- Erros de gravaçãoIn the very last shot of the film the shadow of the camera man or someone else enters the picture from the bottom right.

- Citações

Gerard: Lend him to us.

Marie's mother: He's worked enough. He's old. He's all I have.

Gerard: Just for a day.

Marie's mother: Besides, he's a saint.

- Versões alternativasRestored in 2014 from the original 35mm negative by the Éclair Group and L.E. Diapason.

- ConexõesEdited into Histoire(s) du cinéma: Seul le cinéma (1994)

- Trilhas sonorasPiano Sonata No.20 in A Major, II. Andantino (D. 959)

Music by Franz Schubert

Performed by Jean-Joël Barbier

Principais escolhas

Faça login para avaliar e ver a lista de recomendações personalizadas

- How long is Au hasard Balthazar?Fornecido pela Alexa

Detalhes

Bilheteria

- Faturamento bruto nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 45.406

- Fim de semana de estreia nos EUA e Canadá

- US$ 8.436

- 19 de out. de 2003

- Faturamento bruto mundial

- US$ 45.406

- Tempo de duração1 hora 35 minutos

- Cor

- Mixagem de som

- Proporção

- 1.66 : 1

Contribua para esta página

Sugerir uma alteração ou adicionar conteúdo ausente