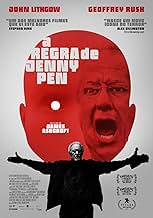

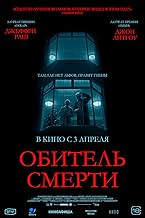

Confined to a secluded rest home and trapped within his stroke-ridden body, a former Judge must stop an elderly psychopath who employs a child's puppet to abuse the home's residents with dea... Read allConfined to a secluded rest home and trapped within his stroke-ridden body, a former Judge must stop an elderly psychopath who employs a child's puppet to abuse the home's residents with deadly consequences.Confined to a secluded rest home and trapped within his stroke-ridden body, a former Judge must stop an elderly psychopath who employs a child's puppet to abuse the home's residents with deadly consequences.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Awards

- 1 win & 1 nomination total

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured review

At times, "The Rule of Jenny Pen" reminded me of post-1970s police and hospital procedurals with their focus on the sheer motion of their environments: the noise of the phones, the constant typewriter clacking, papers being shuffled and placed on desks, the conversations of different persons blending together, etc.

TROJP, set in a New Zealand elder care facility ("Royal Pine Mews"), does something similar, often purposefully failing to show us, or provide audio to, "key" events. For example, in one early scene, the head nurse is speaking with "Dave" (John Lithgow) about something sensitive enough that she ushers him outdoors in order to communicate. Given that the conversation takes place right after a fraught encounter between Dave and "Stefan" (Geoffrey Rush), we would assume it's pretty important to the story.

But we cannot hear what Dave and the nurse are saying (or even see the two entirely) because we are soon separated from them by a glass door and there is another conversation taking place in the same frame and closer to the viewer. TROJP takes this path often, framing both the camera position and the audio in a manner that demands that the viewer search for the main event and make an effort to pay attention. Is TROJP less a horror movie than an "art house" movie?

Not really. At work beneath this buzzing, contemporary stylistic exterior is a pretty familiar (and simple) story: An older man of privilege (Stefan) is to lose some of his privilege and enter a new world in which he will be confronted by a seemingly unaccountable enemy (Dave).

TROJP opens with then-judge Stefan meting out a prison sentence to a child molester. Stefan then coldly reprimands the defendant's wife only to begin suffering the stroke that debilitates him and forces him into Royal Pine Mews. Now dependent upon others, Stefan's old character habits prove hard to break. He snubs his roommate, treats the staff like personal secretaries and eats his communal meals from behind an old book that he positions in front of face at all times. Stefan is clearly separating himself from, if not rejecting outright, his fellow patients. And of course, when he finally needs assistance, he finds that those he has snubbed and ignored have far better memories of past events than does Judge Stefan. He indeed is an island of one.

Lithgow, sporting a somewhat clumsy accent and a shock of grey hair, becomes Stefan's foil. Where Stefan wears his disdain on his sleeve, Dave hides from the world from behind a small hand-held doll, "Jenny Pen," that he uses to interface with his surroundings. (Jenny's eyes glow. The camera often lingers on Dave's flint-blue eyes in what must be a deliberate comparison.) By day, Dave acts like someone who suffers from dementia or a developmental disability. By night, however, Dave perks to life, lurking the halls with his devil doll and terrorizing other patients by sneaking into their rooms to assault them, steal from them and demand that they pay homage to Jenny. The patients fear Dave. And they are right to do so. Stefan is a pompous ass, but Dave appears to be a sociopath. And Dave immediately decides that Stefan should be one of his targets.

Now if there is a problem here it is in the use of an obvious conceit that viewers will be quick to note: the patients know what a terror Dave is, but the staff just don't seem to ever notice. Or do they, but simply do not care? This question is never addressed, much less explained. It's a real problem for a film that tries to bridge the gap between realism and psychological thriller. There are some extended scenes involving physical violence where it begs credulity that no staff member would be present to witness the goings-on. Accordingly, we can guess how the story might end, as the good judge begins to take matters into his own hands. He enters Dave's room toward the end of the film to begin meting out his own brand of justice.

But the disjuncture between the realism of what patients experience in elder care facilities and the almost cartoonish excesses of Dave's behavior involves more than just a plot hole. Toward the end I found myself asking what, exactly, the point was to all of this unpleasantness? TROJP clearly aspires to more than just thrills and scares. But to what end? Is TROJP a rumination on how we treat the elderly? How patients in these facilities experience loss, confusion, powerlessness and the futility of appealing to the professionalism of the very institutions that are there to help them?

These are interesting and important questions, and ones we don't usually expect to find in a horror movie. However, I cannot say that TROJP speaks to them in any sustained fashion, which is odd considering all the work the camera does to illuminate the boredom, sadness and confusion of the Royal Pine Mews residents. In the end, Dave (unlike Stefan) seems to function as little more than a horror movie archetype: he is the writhing, twisting monster with no discernible past who simply happens to always be at the right place at the right time to attack his victims before slinking off undetected. He has no "personality" beyond the joy he takes in wreaking havoc - a sort of "Joker" figure (Batman). TROJP is certainly a stylish and interesting film. But it never quite rises above its basic premise of the self-righteous judge meeting the unaccountable bully.

TROJP, set in a New Zealand elder care facility ("Royal Pine Mews"), does something similar, often purposefully failing to show us, or provide audio to, "key" events. For example, in one early scene, the head nurse is speaking with "Dave" (John Lithgow) about something sensitive enough that she ushers him outdoors in order to communicate. Given that the conversation takes place right after a fraught encounter between Dave and "Stefan" (Geoffrey Rush), we would assume it's pretty important to the story.

But we cannot hear what Dave and the nurse are saying (or even see the two entirely) because we are soon separated from them by a glass door and there is another conversation taking place in the same frame and closer to the viewer. TROJP takes this path often, framing both the camera position and the audio in a manner that demands that the viewer search for the main event and make an effort to pay attention. Is TROJP less a horror movie than an "art house" movie?

Not really. At work beneath this buzzing, contemporary stylistic exterior is a pretty familiar (and simple) story: An older man of privilege (Stefan) is to lose some of his privilege and enter a new world in which he will be confronted by a seemingly unaccountable enemy (Dave).

TROJP opens with then-judge Stefan meting out a prison sentence to a child molester. Stefan then coldly reprimands the defendant's wife only to begin suffering the stroke that debilitates him and forces him into Royal Pine Mews. Now dependent upon others, Stefan's old character habits prove hard to break. He snubs his roommate, treats the staff like personal secretaries and eats his communal meals from behind an old book that he positions in front of face at all times. Stefan is clearly separating himself from, if not rejecting outright, his fellow patients. And of course, when he finally needs assistance, he finds that those he has snubbed and ignored have far better memories of past events than does Judge Stefan. He indeed is an island of one.

Lithgow, sporting a somewhat clumsy accent and a shock of grey hair, becomes Stefan's foil. Where Stefan wears his disdain on his sleeve, Dave hides from the world from behind a small hand-held doll, "Jenny Pen," that he uses to interface with his surroundings. (Jenny's eyes glow. The camera often lingers on Dave's flint-blue eyes in what must be a deliberate comparison.) By day, Dave acts like someone who suffers from dementia or a developmental disability. By night, however, Dave perks to life, lurking the halls with his devil doll and terrorizing other patients by sneaking into their rooms to assault them, steal from them and demand that they pay homage to Jenny. The patients fear Dave. And they are right to do so. Stefan is a pompous ass, but Dave appears to be a sociopath. And Dave immediately decides that Stefan should be one of his targets.

Now if there is a problem here it is in the use of an obvious conceit that viewers will be quick to note: the patients know what a terror Dave is, but the staff just don't seem to ever notice. Or do they, but simply do not care? This question is never addressed, much less explained. It's a real problem for a film that tries to bridge the gap between realism and psychological thriller. There are some extended scenes involving physical violence where it begs credulity that no staff member would be present to witness the goings-on. Accordingly, we can guess how the story might end, as the good judge begins to take matters into his own hands. He enters Dave's room toward the end of the film to begin meting out his own brand of justice.

But the disjuncture between the realism of what patients experience in elder care facilities and the almost cartoonish excesses of Dave's behavior involves more than just a plot hole. Toward the end I found myself asking what, exactly, the point was to all of this unpleasantness? TROJP clearly aspires to more than just thrills and scares. But to what end? Is TROJP a rumination on how we treat the elderly? How patients in these facilities experience loss, confusion, powerlessness and the futility of appealing to the professionalism of the very institutions that are there to help them?

These are interesting and important questions, and ones we don't usually expect to find in a horror movie. However, I cannot say that TROJP speaks to them in any sustained fashion, which is odd considering all the work the camera does to illuminate the boredom, sadness and confusion of the Royal Pine Mews residents. In the end, Dave (unlike Stefan) seems to function as little more than a horror movie archetype: he is the writhing, twisting monster with no discernible past who simply happens to always be at the right place at the right time to attack his victims before slinking off undetected. He has no "personality" beyond the joy he takes in wreaking havoc - a sort of "Joker" figure (Batman). TROJP is certainly a stylish and interesting film. But it never quite rises above its basic premise of the self-righteous judge meeting the unaccountable bully.

- captainpass

- Mar 29, 2025

- Permalink

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaDirector John Ashcroft said the film is ultimately about tyranny and described the story as the rise of a dictator in the least of likely places.

- Quotes

Dave Crealy: We don't stop playing because we get old, we get old because we stop playing.

- ConnectionsReferences The Sum of All Fears (2002)

- SoundtracksKa Mate

Composed by Te Rauparaha

Courtesy of Ngati Toa Rangatira

Thanks to Ihaia Ropata, Te Rauparaha Horomona, Taku Parai, Anahera Parata

- How long is The Rule of Jenny Pen?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Language

- Also known as

- Jenny Pen'in Kuralı

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $433,817

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $254,953

- Mar 9, 2025

- Gross worldwide

- $568,925

- Runtime1 hour 44 minutes

- Color

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content