IMDb RATING

7.2/10

1.8K

YOUR RATING

100.000.000 peasants - illiterate, poor, hungry. There comes a day when one woman decides that she can live old life no longer. Using ways of new Soviet state and industrial progress she cha... Read all100.000.000 peasants - illiterate, poor, hungry. There comes a day when one woman decides that she can live old life no longer. Using ways of new Soviet state and industrial progress she changes life and labor of her village.100.000.000 peasants - illiterate, poor, hungry. There comes a day when one woman decides that she can live old life no longer. Using ways of new Soviet state and industrial progress she changes life and labor of her village.

- Awards

- 1 win total

- Directors

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured review

This is a very conscious change in direction from Eisenstein and his codirector Grigori Aleksandrov. Eisenstein's first three films (including October: Ten Days that Shook the World which was also codirected by Aleksandrov) had no main characters. They barely had characters at all. Well, now, in The General Line, the entire film revolves around one character, a woman farmer. The pair do not remove themselves from the propaganda, but they do change what they're propagandizing for. The former were for revolution directly. This is for acceptance of the new Soviet farming system as better, more efficient, more technologically advanced, and more wealth-generating than any other system available (mostly the old, Tsarist feudal system).

Martha (Martha Lapkina) lives in rural Russia after the fall of the Tsar, and she watches the family farm split into parts upon the death of her father, most going to her two brothers. She has a vision, though, and that vision is the kolkhoz, the Soviet communal farms that will lead to progress. Against her are the old orders, mostly exemplified by the Orthodox Church and the old land owners, the kulaks, the second lowest of the old system who were now the highest of the new before the Soviets could fix things. That progress goes through the arrival of a milk separator that eases the labor of turning milk into cream, the purchase of a bull to make the farm a bovine commune, and the purchase of a tractor to ease the labor in the fields.

Each event is effectively a short film on its own with its own ebbs and flows, one of the reasons why the film doesn't work quite as well as something like Battleship Potemkin. However, the individual sequences are really masterclasses in Eisenstein's editing. The standout is probably the separator sequence. The farmers, including Martha, are introduced to this new machine by the local commissar (Ivan Yudin), and we watch as the farmers give up some of their milk to this unknown machine. It slowly works, the commissar turning the gear over and over with Eisenstein cross-cutting all over the place to build tension, until the two dispensing tubes start releasing the cream and the milk, separated with much less waiting than the old process was. Technological progress, the new, wins over the old.

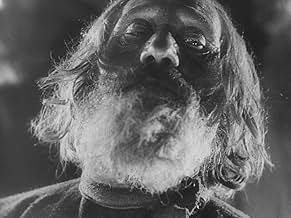

The most dominant display of the old, in my mind, is a religious procession. The farmers remain in the middle of the road as the religious parade icons of religious figures directly over them, Eisenstein making it obvious that the Church considers itself more than the people who degrade themselves before it. The procession goes to a hill where the chief priest promises a miracle which he times with a cloud which allows him to surreptitiously do some stuff, but Martha looks up and sees the deception, informing her of the emptiness of religion. All she has is the collective.

She faces different challenges in her efforts, and I found these...curious. Some of them make perfect sense from the perspective of the needs of Soviet propaganda, mostly around the kulaks poisoning the bull. However, the two biggest hurdles for the Soviet collective farm in the latter parts of the film are parts of the...Soviet future. The first is the bureaucracy itself which is a slow-moving machine that does not want to move with any energy in approving their purchase for a tractor (that they have to get permission to buy a tractor is an obvious irony that the film makes no notice of, of course). I mean...this is the most direct and largest portrait that the movie makes of the Soviet state itself...and it needs to be shamed into action. Gonna be honest, I'm shocked this made it to the final cut.

The final thing is the tractor itself. A product of the great Soviet industrial machine, it's presented in the most glamorous terms when it is brought to the farm to be driven by a well-dressed young man (Konstantin Vasilyev). The tractor...immediately breaks down. The young man has to take it apart and fix it, and Martha helps him. Now, there are symbolic things all around this (the farmer and the industry coming together for Russia, the young man shedding his fancy dress for more rural appropriate attire, the people collectively being the power of Russia type stuff), but the larger image is still there: the new Soviet tractor immediately broke down. That's...so bizarre. It's so bizarre that it almost feels satirical, but it can't be. If it survived Soviet censorship, then no one saw it that way.

Anyway, the individual sequences are where the film is the most enjoyable. They just don't connect as well as they should. The middle section, which is essentially just a dream Martha has of a working factory farm, goes on for so long and is such a departure from the actual narrative that my interest just waned tremendously. However, by keeping it to the middle and backloading the film with the most dramatic bits with the tractor helps elevate the depression made by that middle section.

So, Eisenstein shows that he's most interesting in this period as the creator of sequences. I'm honestly not sure what Aleksandrov brings to the production (online there doesn't seem to be much of any information about how they divided any directing responsibilities), but considering he's mostly known for things like musicals of the early sound period, I'd suspect he had a greater hand in the miniatures and larger physical production elements than Eisenstein did. The overall product is interesting and somewhat entertaining. The individual sequences are tours-de-force. The focus on a central character gives the audience something more than general adherence to communist principles to latch onto (she even gets a wedding by the end, which is nice). I think I'm most interested in the film as a look at a different culture, though: 1920s rural Russia.

In some ways, this is my favorite of Eisenstein's silent films, but it's also his least in some other ways.

Martha (Martha Lapkina) lives in rural Russia after the fall of the Tsar, and she watches the family farm split into parts upon the death of her father, most going to her two brothers. She has a vision, though, and that vision is the kolkhoz, the Soviet communal farms that will lead to progress. Against her are the old orders, mostly exemplified by the Orthodox Church and the old land owners, the kulaks, the second lowest of the old system who were now the highest of the new before the Soviets could fix things. That progress goes through the arrival of a milk separator that eases the labor of turning milk into cream, the purchase of a bull to make the farm a bovine commune, and the purchase of a tractor to ease the labor in the fields.

Each event is effectively a short film on its own with its own ebbs and flows, one of the reasons why the film doesn't work quite as well as something like Battleship Potemkin. However, the individual sequences are really masterclasses in Eisenstein's editing. The standout is probably the separator sequence. The farmers, including Martha, are introduced to this new machine by the local commissar (Ivan Yudin), and we watch as the farmers give up some of their milk to this unknown machine. It slowly works, the commissar turning the gear over and over with Eisenstein cross-cutting all over the place to build tension, until the two dispensing tubes start releasing the cream and the milk, separated with much less waiting than the old process was. Technological progress, the new, wins over the old.

The most dominant display of the old, in my mind, is a religious procession. The farmers remain in the middle of the road as the religious parade icons of religious figures directly over them, Eisenstein making it obvious that the Church considers itself more than the people who degrade themselves before it. The procession goes to a hill where the chief priest promises a miracle which he times with a cloud which allows him to surreptitiously do some stuff, but Martha looks up and sees the deception, informing her of the emptiness of religion. All she has is the collective.

She faces different challenges in her efforts, and I found these...curious. Some of them make perfect sense from the perspective of the needs of Soviet propaganda, mostly around the kulaks poisoning the bull. However, the two biggest hurdles for the Soviet collective farm in the latter parts of the film are parts of the...Soviet future. The first is the bureaucracy itself which is a slow-moving machine that does not want to move with any energy in approving their purchase for a tractor (that they have to get permission to buy a tractor is an obvious irony that the film makes no notice of, of course). I mean...this is the most direct and largest portrait that the movie makes of the Soviet state itself...and it needs to be shamed into action. Gonna be honest, I'm shocked this made it to the final cut.

The final thing is the tractor itself. A product of the great Soviet industrial machine, it's presented in the most glamorous terms when it is brought to the farm to be driven by a well-dressed young man (Konstantin Vasilyev). The tractor...immediately breaks down. The young man has to take it apart and fix it, and Martha helps him. Now, there are symbolic things all around this (the farmer and the industry coming together for Russia, the young man shedding his fancy dress for more rural appropriate attire, the people collectively being the power of Russia type stuff), but the larger image is still there: the new Soviet tractor immediately broke down. That's...so bizarre. It's so bizarre that it almost feels satirical, but it can't be. If it survived Soviet censorship, then no one saw it that way.

Anyway, the individual sequences are where the film is the most enjoyable. They just don't connect as well as they should. The middle section, which is essentially just a dream Martha has of a working factory farm, goes on for so long and is such a departure from the actual narrative that my interest just waned tremendously. However, by keeping it to the middle and backloading the film with the most dramatic bits with the tractor helps elevate the depression made by that middle section.

So, Eisenstein shows that he's most interesting in this period as the creator of sequences. I'm honestly not sure what Aleksandrov brings to the production (online there doesn't seem to be much of any information about how they divided any directing responsibilities), but considering he's mostly known for things like musicals of the early sound period, I'd suspect he had a greater hand in the miniatures and larger physical production elements than Eisenstein did. The overall product is interesting and somewhat entertaining. The individual sequences are tours-de-force. The focus on a central character gives the audience something more than general adherence to communist principles to latch onto (she even gets a wedding by the end, which is nice). I think I'm most interested in the film as a look at a different culture, though: 1920s rural Russia.

In some ways, this is my favorite of Eisenstein's silent films, but it's also his least in some other ways.

- davidmvining

- Mar 14, 2025

- Permalink

Storyline

Did you know

- ConnectionsEdited into Sauve la vie (qui peut) (1981)

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- Eski ve Yeni

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Runtime2 hours 1 minute

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content