Proto-cuneiform

Early proto-writing system From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

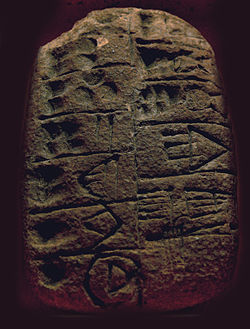

The proto-cuneiform script was a system of proto-writing that emerged in Mesopotamia, eventually developing into the early cuneiform script used in the region's Early Dynastic I period. It arose from the token-based system that had already been in use across the region in preceding millennia. While it is known definitively that later cuneiform was used to write the Sumerian language, it is still uncertain what the underlying language of proto-cuneiform texts was.

History

Summarize

Perspective

Possibly as early as the 9th millennium BC, a token-based system came into use in various parts of the ancient Near East. These evolved into marked tokens, and then into marked envelopes now known as clay bullae.[2][3][4][5] It is usually assumed that these were the basis for the development of proto-cuneiform, as well as of the contemporaneous Proto-Elamite writing system: as many as two-thirds of the tokens discovered have been excavated in Susa, the most important city in what would become Elam. These tokens continued to be used, even after the development of proto-cuneiform and Proto-Elamite.[6][7][8][9][10]

The earliest tablets found, in the Uruk V period (c. 3500 BC), are of a 'numerical' character. They consist only of lists of numbers associated with 18 known signs (circles, triangles etc), sometimes sealed. It has been suggested that they appeared as early as the Uruk IV period and remained in use until the Uruk IVa period.[11] Generally they are called "numerical tablets" or "impressed tablets". They have been mostly found in Susa (75) and Uruk (190) (small numbers in Jemdat Nasr (2), Chogha Mish (1), Tepe Sialk (10), Tutub (1), Khafajah (1), and Mari (1)) including some that lack later Proto-Elamite and proto-cuneiform tablets, like Tell Brak (1), Habuba Kabira (3), Tepe Hissar, Godin Tepe (38), Nineveh (1), and Jebel Aruda (13). A few unprovenanced tablets are held in private collections.[12][13][14][15][16][17] A single fragmentary slab at the Uruk site of Hacınebi Tepe has been proposed as a numerical tablet.[18]

Proto-cuneiform emerged in what is now labeled the Uruk IV period (c. 3300 BC), and its use continued through the later Uruk III period (c. 3200-2900 BC), also called the Jemdat Nasr period. The script slowly evolved over time, with signs changing and merging.[19] It was used for the first time in Uruk, later spreading to additional locations in what is now modern day Iraq, such as Jemdet Nasr, and to Susa in modern day Iran.[20]

With the advent of the Early Dynastic period c. 2900 BC, the standard cuneiform script used to write the Sumerian language emerged, though only about 400 tablets have been recovered from this period; these are mainly from Ur, with a few from Uruk.[21]

It has been suggested that the development of Proto-cuneiform signs was influenced by symbols (motifs) found on earlier cylinder seals. Stamp seals were not considered.[22]

Language

There is a longstanding debate in the academic community regarding when the Sumerian people arrived in Mesopotamia. Partly spurred by linguistic arguments and evidence, overall it is generally clear that a number of fundamental changes occurred in Mesopotamia—such as the use of the plano-convex brick—at the same time the first definitive evidence of the Sumerian language appeared during the Early Dynastic I period. Proto-cuneiform offers no clear clues as to what spoken language it encoded, leading to much speculation, though Sumerian is often assumed.[23][24]

Corpus

Summarize

Perspective

About 170 similar tablets from Uruk V (c. 3500 BC), Susa, and other Iranian sites like Tepe Sialk, are considered to be pre-Proto-Elamite, though bearing similarities to proto-cuneiform.[25] Sign lists and transliterations are less clear for this category.[26]

Like Proto-Elamite, the system's propagation was relatively limited. The vast majority of the proto-cuneiform texts found, about 5000, have been located in archaic Uruk (190 Uruk V, 1776 Uruk IV, 3094 Uruk III), though also in secondary contexts within the Eanna district. The tablets fall primarily into two styles: the earlier (building level IV) set featuring more naturalistic figures, written with a pointed stylus, and the later set (building level III) with a more abstract style, made using a blunt stylus. These correspond to the Late Uruk c. 3100 BC and Jemdet Nasr c. 3000 BC periods respectively.[27][28] Many of the tablets were themselves later used as foundation fill during the construction of the Uruk III Eanna temple complex.[29] It appears that the records were considered to be of transient utility or interest, and were quickly disposed of. The difficult stratigraphy has brought about a change from referring to tablets based on excavation layer to one of calling them script phase IV and III. Similarly to the tablets, clay seals previously used to secure vessels and doors ended up in the fill after being removed.[30] The sites and analysis of sealing has led to suggestions that the tablets originated elsewhere and ended up at Uruk, where they were discarded.[31]

A smaller number of tablets were found in Jemdet Nasr (2 Uruk V, 236 Uruk III), Umma (398 Uruk III), Eshnunna (2 Uruk III), Larsa (23 Uruk III), Kish (5 Uruk III), and Tell Uqair (39 Uruk III).[32][33][34] They tend to be less fragmentary and are sometimes found in stratified contexts. Some have made their way into various private and public collections: the provenance for some can be determined from internal clues, but for some the origin city is unknown.[35][36] For example, in 1988 ninety complete well-preserved tablets from the Swiss Erlenmeyer Collection in Basel were auctioned off with most ending up in public collections. The majority, fifty eight, were purchased by the State of Berlin and transferred to the Vorderasiatisches Museum as a permanent loan. A few others ended up at the British Museum and Louvre Museum.[37][38]

A notable exemplar was found by Langdon during his excavation in the 1920s, often called the "Kish tablet". A plaster-cast of the artifact is presently held in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, with the original at the Baghdad Museum. Its date of origin is unclear.[39]

Some tablets were sealed using a cylindrical seal.[40] Two Uruk period clay sealings found at Ur had a single proto-cuneiform sign, ŠAM2.[41]

State of decipherment

Summarize

Perspective

To decipher an unknown, fully functional writing system, scholars usually need some knowledge of the underlying spoken language, some bilingual texts, and a large corpus. Proto-cuneiform was not accessible in any of these ways, but decipherment was possible because it was not a full writing system, but a specialized notation for economic administration. Its texts were stereotyped and concrete, such as lists of items.[42][43]

Already in 1928 with the first publication of texts, a numerical sign list had been developed, based on similarity to the signs of Fara, the earliest cuneiform texts which were the immediate successors of Proto-cuneiform. The sexagesimal numerals and area numbers were also essentially the same.[44] The mathematical system of proto-cuneiform and Proto-Elamite was largely deciphered over a few decades beginning in the 1970s.[45][46][47][48] Some details remain obscure, and several generally agreed-upon details remain contested. For example, the (ŠE system E) is thought to be a capacity measure, but this has been challenged because it is only found in the Uruk IV layers, not the later Uruk III, and it lacks the markers of a capacity measure.[49][50]

As an example of the current partial state of decipherment, a small tablet found at Uruk (The Kushim referenced may be an individual or title):[51]

3(N48) 1(N34) 6(N14) 1(N01) 1(N39a) , U4x(3(N14).7(N01)) SZEa DUBa LAGABbxLAGABb (KUb1 SZIMa)a SZAm2 - Transliteration

5617 1/5 N1’s, exchange barley, 37 months, Kushim’s final account. ca. 135,000 liters - Translation

Sign Inventory

Summarize

Perspective

Currently there are about 2000 known proto-cuneiform signs: about 350 numerical, 1100 individual ideographic, and 600 complex (combinations of individual signs).[52] The non-numerical signs are attested in about 40,000 occurrences. There was a high degree of heterogeneity in sign usage: about 530 signs are only attested once, about 610 two to ten times, 370 attested 11 to 100 times, and about 104 signs attested more than 100 times.[43] Many signs have been identified including those for barley and emmer wheat.[53] The most common signs are ENa, GALa, and ŠEa.[54]

| DU7 | SAL | SUH3 | NIGIN | ERIN | KU6 | DIN | BULUG | NI2 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| IGI | TIDNUM | GU2 | U4 | DAM | RI | IL | AL | KAK |

|

|

|

| |||||

| MASZ2 | DI | SHUBUR | A | HI | SIKIL | TE | BAD | AMA |

|

|

|

Numbers

The underlying numeric base of the Proto-cuneiform, like later cuneiform, is sexagesimal (base 60).[55][56] Earlier researchers believed that this system rose out of an earlier decimal (base 10) substratum but that idea has now lost currency.[57]

Different products used different measurement systems, which could change with the context. In a single tablet the (Bisexagesimal System B) could be used for grain rations, (ŠE system Š) for barley, and (ŠE system Š") for emmer wheat. Another was (ŠE system C) for capacity, typically of grain.[58] There were thirteen numerical systems in total (Sexagesimal, Sexagesimal S', Bisexagesimal, Bisexagesimal B*, GAN2, EN, U4, ŠE, ŠE', ŠE", ŠE*, DUGb, DUGc) of which the contemporary Proto-Elamite writing system used only seven, and only half of the sixty proto-cuneiform numerical signs.[59][60]

Texts

Administrative

The largest group of Proto-cuneiform texts (about 2000 from the Uruk IV period and 3600 from Uruk III) are accounts (economic records).[61] They involve a variety of items including people, livestock, and grain. Confusingly, there are often multiple ways to write things. For example, people can be listed by gender and age (adult, minor, baby); or without gender by a number of age groups (0–1, 3–10 etc.).[62]

Miscellaneous

Another large category (with around a dozen examples in Uruk IV, and approximately 750 in Uruk III)) are called "lexical lists", which appeared during Uruk IV but proliferated in Uruk III.[63] These are lists of items in a given physical category: metals, cities, tools.[64][65][66][67] Examples persisted into Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian times.[68][69][70]

Publications

Summarize

Perspective

The proto-cuneiform texts from Uruk were published in a series of books (ATU)

- ATU 1. Adam Falkenstein, "Archaische Texte aus Uruk", Berlin und Leipzig: Deutsche Forschungsgemein-schaft, Kommissionsverlag Otto Harrassowitz, 1936

- ATU 2. M. W. Green und Hans J. Nissen, unter Mitarbeit von Peter Damerow und Robert K. Englund, "Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk", Berlin, 1987 ISBN 978-3786114390

- ATU 3. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von Peter Damerow, "Die Lexikalischen Listen der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk", Berlin, 1993 ISBN 978-3786116875

- ATU 4. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen, "Katalog der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk"

- ATU 5. Robert K. Englund unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaic Administrative Texts from Uruk: The Early Campaigns", Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1994 ISBN 978-3786117452

- ATU 6. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaische Verwaltungstexte aus Uruk: Vorderasiatisches Museum II", Berlin, 2005 ISBN 978-3786125211

- ATU 7. Robert K. Englund und Hans J. Nissen unter Mitarbeit von R. M. Boehmer, "Archaische Verwaltungstexte aus Uruk: Die Heidelberger Sammlung", Berlin, 2001 ISBN 978-3786124023

And from other sites (MSVO)

- MSVO 1. Robert K. Englund, Jean-Pierre Grégoire, and Roger J. Matthews, "The proto-cuneiform Texts from Jemdet Nasr I: Copies, Transliterations and Glossary", Materialien zu den frühen Schriftzeugnissen des Vorderen Orients Bd. 1. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1991 ISBN 9783786116462

- MSVO 2. Matthews, R. J, "Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur", Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1993 ISBN 978-3786116868

- MSVO 3. Damerow, P. & Englund, R. K., "The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from the Erlenmeyer Collection" Berlin.

- MSVO 4. Robert K. Englund and Roger J. Matthews, "Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Diverse Collections", Materialien zu den frühen Schriftzeugnissen des Vorderen Orients Bd. 4. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1996 ISBN 978-3786118756

- CUSAS 1. Salvatore F. Monaco, "The Cornell University Archaic Tablets (Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology)", Eisenbrauns, 2007 ISBN 978-1934309001

- CUSAS 21. Salvatore Monaco, "Archaic Bullae and Tablets in the Cornell University Collections (Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology)", 2014 ISBN 978-1-934309-55-1

- CUSAS 31. Salvatore F. Monaco, "Archaic Cuneiform Tablets from Private Collections (Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology)", 2016 ISBN 978-1-934309-65-0

Unicode

A Unicode block encoding proto-cuneiform (Uruk III and Uruk IV) was initially proposed in 2020.[52] but has not yet been formally accepted by the consortium, though character encoding for later forms of cuneiform have been formalized.[71][72][73][74][75]

Gallery

- Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.583

- Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.602

- Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.606

- Jemdet Nasr tablet AN1926.564

- Louvre Uruk III tablette écriture précunéiforme AO19936

- Precuneiforme tablet-AO 8856-IMG 9155-gradient

- Tablette precuneiforme AO 2753

- Clay Tablet - Louvre - AO29562

- Clay Tablet - Louvre - AO29560

- Five day ration list - Jemdet Nasr

- Numerical and proto cuneiforms tablets - Oriental Institute

- Clay tablet, lexical text, listing 58 different terms for pig. From Uruk, Iraq. 3200 BCE. Pergamon Museum

- Uruk period administrative tablet

- Tontäfelchen Mesopotamien 3200vChr 2

- Tablette numerale Sialk IV

- Proto-cuneiform Vessels list

- Vessels exical list tablet

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.